The Mechanics of Compression: How 100GB Becomes 25GB

A deep dive into the mathematical 'magic' behind data compression, from Huffman Coding to the architectural differences between ZIP and TAR.GZ.

The Mechanics of Compression: How 100GB Becomes 25GB

In an era of 4K streaming and massive cloud databases, we often take for granted that a 100GB backup can be shrunk down to 25GB. It isn’t magic—and it isn’t just “squeezing” bits. It’s a careful process of spotting patterns, removing redundancy, and using mathematical shorthand so that the same information takes less space. This post explains how that works in plain terms, so you can understand what happens under the hood when you zip a folder or stream a video.

1. The Core Idea: Redundancy Is Waste

At its heart, compression is about efficiency. Most data is repetitive. The same words, phrases, or pixel patterns show up again and again. If the computer has already seen a pattern once, it doesn’t need to store it again in full—it can refer back to it or describe it in fewer bits.

Think of a recipe that says “add salt” five times. You could write “add salt” five times, or you could write “add salt (×5).” The second version carries the same information in less space. Compression algorithms do something similar: they find repetition and describe it more compactly.

So the main job of any compression scheme is to find redundancy and encode it in fewer bits without losing the ability to recover the original data when needed.

A Real-Life Example: Compressing a Book with Repeated Words

Imagine a book where the same words appear again and again. Words like "the," "and," and "to" might show up thousands of times. Instead of writing the full word every time, we could agree on a legend at the start and replace each repeated word with a short sub-symbol. Anyone with the legend can reconstruct the original text exactly.

Suppose we define a small dictionary at the top of the page:

Legend: @ = the | # = and | % = to | § = of

Now take a normal sentence and "compress" it by substituting:

Original (longer): "The king and the queen went to the castle and stayed there for the rest of the day."

Compressed (shorter): "@ king # @ queen went % @ castle # stayed there for @ rest § @ day."

We still have the same meaning, but we used one character (@, #, %, §) wherever a repeated word appeared. The legend is the "dictionary"—it has to be stored or sent once so the reader can decode. For a whole book, if "the" appears 2,000 times, we save (3 − 1) × 2,000 = 4,000 characters just on that one word. Add "and," "to," "of," and other frequent words, and the book shrinks noticeably without losing a single word.

This is exactly the idea behind dictionary coding and Huffman-style compression: find what repeats, assign it a short code, and use that code everywhere. Real compressors do this automatically; they don't need a human to write the legend.

A real experiment from the wild: Researchers applied this idea to the full text of "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" by Lewis Carroll. They treated each word as a symbol, counted how often it appeared, and assigned shorter codes to the most frequent words (like "the," "and," "to," "a") and longer codes to rare words (like "wretched," "yawned"). The result: the text went from 164 KB down to 109 KB—about one-third smaller—with no information lost (Huffman-coding English words, Project Nayuki—includes original text from Project Gutenberg, input/output file sizes, and codebook samples). The same technique—replace repeated words with shorter symbols, and keep a mapping so we can decode—is what powers the compression we use every day in ZIP files and beyond.

2. Lossless vs. Lossy: Two Different Goals

Before diving into algorithms, it helps to know that compression splits into two families: lossless and lossy. The choice depends on whether you can afford to lose any information.

Lossless Compression: Every Bit Preserved

Lossless compression means that after you decompress, you get back exactly the original data—every bit. Nothing is discarded.

- How it works: The algorithm finds statistical redundancy (repeated or predictable patterns) and encodes them more efficiently. Decompression reverses the process and reconstructs the original stream.

- When to use it: Whenever you cannot afford to lose information—source code, text files, databases, executables, legal documents, medical data, or images where every pixel must stay exact (e.g. PNG for graphics, FLAC for audio).

- Common formats: ZIP, GZIP, PNG, GIF (for lossless use), FLAC.

So when you compress 100GB of source code or logs to 25GB with a lossless tool, you can later decompress and get back the same 100GB bit-for-bit.

Lossy Compression: Smaller Files, Imperceptible Loss

Lossy compression discards some information on purpose. What you get back is an approximation of the original—close enough for human perception, but not identical.

- How it works: The algorithm keeps what matters for the intended use (e.g. what the eye or ear notices) and drops “invisible” or less important detail—e.g. colors we can’t easily tell apart, or sounds masked by louder ones.

- When to use it: Media where small quality loss is acceptable—photos (JPEG), music (MP3, AAC), video (H.264, VP9). Streaming and storage would be far heavier without lossy compression.

- Common formats: JPEG, MP3, AAC, H.264, VP9.

For the rest of this post we focus on lossless compression—the kind that powers ZIP, GZIP, and the 100GB→25GB backup scenario—and then briefly touch how video combines similar ideas with lossy temporal compression.

3. The Building Blocks: Huffman Coding and LZ77

Most modern lossless compressors (including the ones inside ZIP and GZIP) combine two ideas:

- Dictionary / back-reference coding (e.g. LZ77): “I’ve seen this phrase before; refer back to it.”

- Entropy coding (e.g. Huffman): “Frequent symbols get short codes; rare symbols get longer codes.”

Together they form algorithms like DEFLATE (used in ZIP and GZIP): first reduce repetition with something like LZ77, then shorten the remaining stream with Huffman (or similar) coding.

3.1 Huffman Coding: Short Codes for Common Symbols

In normal text encoding (e.g. ASCII or UTF-8), every character uses the same number of bits (e.g. 8 bits per character). So the letter “E” and the letter “Z” both cost 8 bits, even though “E” appears far more often in English text. That’s wasteful: we’re spending the same budget on rare and common symbols.

Huffman coding fixes that by giving variable-length codes: frequent symbols get shorter codes, rare symbols get longer codes. On average, the whole message uses fewer bits.

One crucial constraint: no code is allowed to be a prefix of another. So if “E” is encoded as 10, then no other character’s code can start with 10 (e.g. no 100 or 101). That way, when we read the compressed stream left-to-right, we always know where one symbol ends and the next begins—no need for extra separators (unlike Morse code, which needs pauses between letters).

A simple way to build such codes is with a binary tree: each character is a leaf, and the path from the root to that leaf (e.g. left=0, right=1) is its code. The algorithm builds the tree from the bottom up, repeatedly grouping the two least frequent symbols (or groups) until everything is in one tree. Frequent characters end up near the root (short path); rare ones end up deeper (long path).

Conceptually:

// Standard 8-bit encoding (e.g. ASCII): every character uses 8 bits

"E" = 01000101 (8 bits)

"Z" = 01011010 (8 bits)

// Huffman encoding (example): frequent letters get shorter codes

"E" = 10 (2 bits) ← common in English

"Z" = 111010 (6 bits) ← rare, so longer code

So Huffman doesn’t “invent” new information; it represents the same information in fewer bits by exploiting how often each symbol appears.

3.2 LZ77: “I’ve Seen This Before—Point Back to It”

Huffman only shortens symbols based on frequency. It doesn’t remove repeated phrases. That’s where LZ77 (and family) comes in.

LZ77 keeps a sliding window of recently seen data. As it reads the input, it looks for the longest match between:

- what’s coming next (the “look-ahead” buffer), and

- what it has already seen (the “search” buffer).

When it finds a match, it doesn’t output the phrase again. Instead it outputs a back-reference: a pair (distance, length) meaning “go back distance bytes and copy length bytes.” The decoder can then reconstruct the phrase from earlier in the stream.

So the stream becomes a mix of:

- Literal bytes (when there’s no useful match), and

- Back-references (when a phrase repeats).

Example:

Input: "The quick brown fox jumps over the quick dog"

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

"the quick" appears twice

Compressed idea:

Literals: "The quick brown fox jumps over "

Back-reference: (distance=31, length=9) → copy 9 bytes from 31 bytes ago

Literals: " dog"

After this step, the stream has fewer bytes but still contains the same information. Then Huffman (or similar) is applied to that stream to shorten the representation of literals and back-reference pairs—that’s DEFLATE in a nutshell.

4. ZIP vs. TAR.GZ: Same Ideas, Different Packaging

Both ZIP and TAR.GZ use lossless compression (often DEFLATE/GZIP-style), but they package files differently. That difference affects compression ratio and how you can access files.

ZIP: One File at a Time

ZIP compresses each file separately and then puts them in one archive, with a central directory so you can list and extract individual files.

- Pros: Random access. You can extract

image_402.jpgfrom a 50GB archive without reading or decompressing the rest. Good for browsing and pulling single files. - Cons: The compressor never looks across file boundaries. If 100 files are nearly identical, ZIP may store 100 separate compressed versions and miss shared patterns. So total size can be larger than a “solid” archive.

So ZIP is great when you need per-file access and broad compatibility (e.g. Windows, macOS, Linux).

TAR.GZ: One Big Stream (Solid Archive)

TAR.GZ is a two-step process:

- TAR (Tape Archiver): Concatenate all files into one continuous stream (no compression yet). This is a “solid” archive—one long byte stream.

- GZIP: Compress that entire stream with DEFLATE (LZ77 + Huffman) as if it were a single file.

Because GZIP sees the whole project as one stream, it can find patterns that span many files. A repeated header in file_A.txt can be used to compress the same header in file_Z.txt. That’s why you can get a much better ratio—e.g. 100GB down to 25GB—when you have lots of similar or repeated content across files.

Trade-off: to get any file out of a TAR.GZ, you typically have to decompress from the beginning up to that file. There’s no cheap “jump to file 402” as in ZIP.

# Step 1: Bundle everything into one stream (size unchanged)

tar -cvf backup.tar ./my_project

# Step 2: Compress that whole stream

gzip backup.tar

# Result: backup.tar.gz — one compressed stream

When to use TAR.GZ: Backups, source tarballs, logs, or any case where you want maximum compression and usually extract the whole archive (or don’t mind decompressing from the start to reach a file). Common on Linux and in DevOps pipelines.

When to prefer ZIP: When you need random access to individual files or maximum compatibility with non-Unix systems.

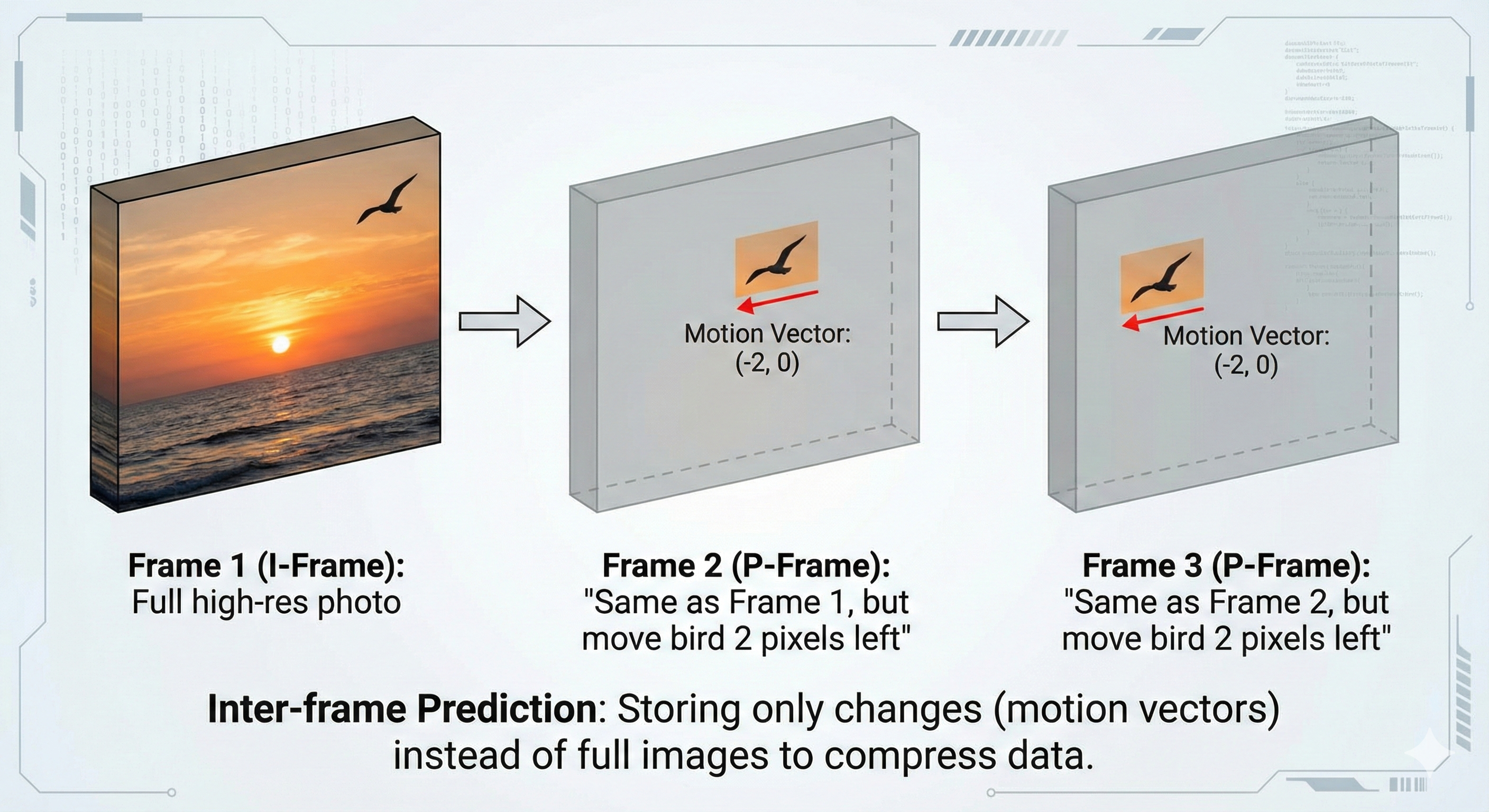

5. How Video Compression Goes Further: Temporal Redundancy

Video has a special kind of redundancy: between frames, most of the image doesn’t change. Only moving parts (and lighting changes) differ. So instead of storing every frame in full, modern codecs (e.g. H.264) use temporal compression: store one full frame, then for the next frames store mainly what changed.

Roughly:

- I-frames (Intra-frames): Full frames—like a JPEG image. They don’t depend on other frames. Used as anchors so you can seek or recover from errors.

- P-frames (Predictive): Encoded as “differences” from a previous frame (or I-frame). Much smaller than a full frame.

- B-frames (Bi-predictive): Use both past and future frames to predict the current frame, so they can be even smaller.

So conceptually:

Frame 1 (I): Full image of a sunset

Frame 2 (P): “Same as Frame 1, but the bird moved 2 pixels left”

Frame 3 (P): “Same as Frame 2, but the bird moved 2 pixels left”

…

Total stored: one full frame + many small “deltas” and motion vectors

That’s temporal compression. Video also uses spatial compression inside each frame (similar in spirit to JPEG). Together, temporal + spatial (and often lossy choices) let streaming and storage stay practical at 1080p and 4K.

6. Wrapping Up

Compression is the invisible engine behind smaller backups, faster transfers, and watchable video. The main ideas are:

- Redundancy is removed or shortened: repeated phrases become back-references (LZ77), and frequent symbols get short codes (Huffman).

- Lossless (ZIP, GZIP, PNG) keeps every bit; lossy (JPEG, MP3, H.264) trades a bit of quality for much smaller size.

- ZIP compresses file-by-file for random access; TAR.GZ compresses one solid stream for better ratio when you don’t need per-file random access.

- Video adds temporal compression: store full frames rarely, and mostly store changes between frames.

Understanding these mechanics helps you choose the right format—whether you’re optimizing Next.js assets, shipping backups to S3, or tuning video encoding—and demystifies how 100GB can become 25GB without losing a single bit.

written using AI tools

Share this post

Backend engineer at Initializ.ai — building scalable systems with Go, Elixir, and Kubernetes. Writing about distributed systems, AWS, and the bugs that cost me hours.